Some of us have just spent the past several evenings in the company of an 8th-century monk who composed a long and beautiful hymn of repentance. Several Orthodox churches, especially of the Slavic tradition, devote the first four evenings of Lent to the singing of The Great Canon of St. Andrew of Crete.

It’s all in the first-person singular. It’s about me, my sinfulness, and my lack of repentance. It opens with what sounds like a rhetorical question from someone entirely overwhelmed: “where do I even begin…”:

How shall I begin to mourn the deeds of my wretched life?

What can I offer as first-fruits of repentance?

And then, we do in fact begin. Starting with Adam and Eve, the Canon proceeds to take us through the entire Bible, Old and New Testaments, with examples of sinners I have imitated, and saints whose example I’ve failed to follow:

My transgressions rival those of first-created Adam,

and because of my sins

I find myself naked of God and of His everlasting Kingdom.… I have reminded you, my soul, from the books of Moses,

how the world was created,

and from accounts throughout the Old Testament

have shown examples of both the righteous and the unrighteous.

But of these you have imitated the latter rather than the former and thereby have sinned against your God.

We unite our voices to the author’s serial self-condemnations, at services in dark, candle-lit churches, every evening during what we call “Clean Week.”

And here’s the puzzling thing: for a great number of people, of a wide variety of ages and dispositions, these are some of the most cherished services of the whole church year. People love them. Here are just a couple of reasons why it might be that people are attracted to these deeply penitential events.

1) They hold nothing back. They are occasions for complete surrender. These aren’t times where we have to devise some kind of clever excuse for why we had this or that bitter thought, why we yielded to this or that temptation. We just admit it all. And this is ultimately easier, cleaner, and more cathartic.

2) They are communal. Each of us says “I have sinned.” That makes a community of “I’s” who together bring ourselves before God. We are a community being saved.

3) They remind us that God is merciful. If God were strict to judge, we would deserve condemnation. And our only hope lies in God’s mercy, which he shows us in the very same Scriptures that condemn us. And it is a sure hope.

4) They remind us that we were created in beauty and dignity, which means that—by God’s grace and through our repentance—we may be restored to our true glory, in God’s own image.

But ultimately, there’s something more fundamental at play, that makes these services so beautiful and so beloved. And that was expressed by a friend who made the following comment on my Facebook wall a couple of years ago:

Somehow the distance from woundedness to joy is shorter than the distance from happiness to joy.

I find that to be pretty profound, and worthy of meditation. It’s one more way of making that observation that the journey towards a searching confession of wrongdoing and genuine compunction is accompanied by consolation, relief, and strangely enough, joy.

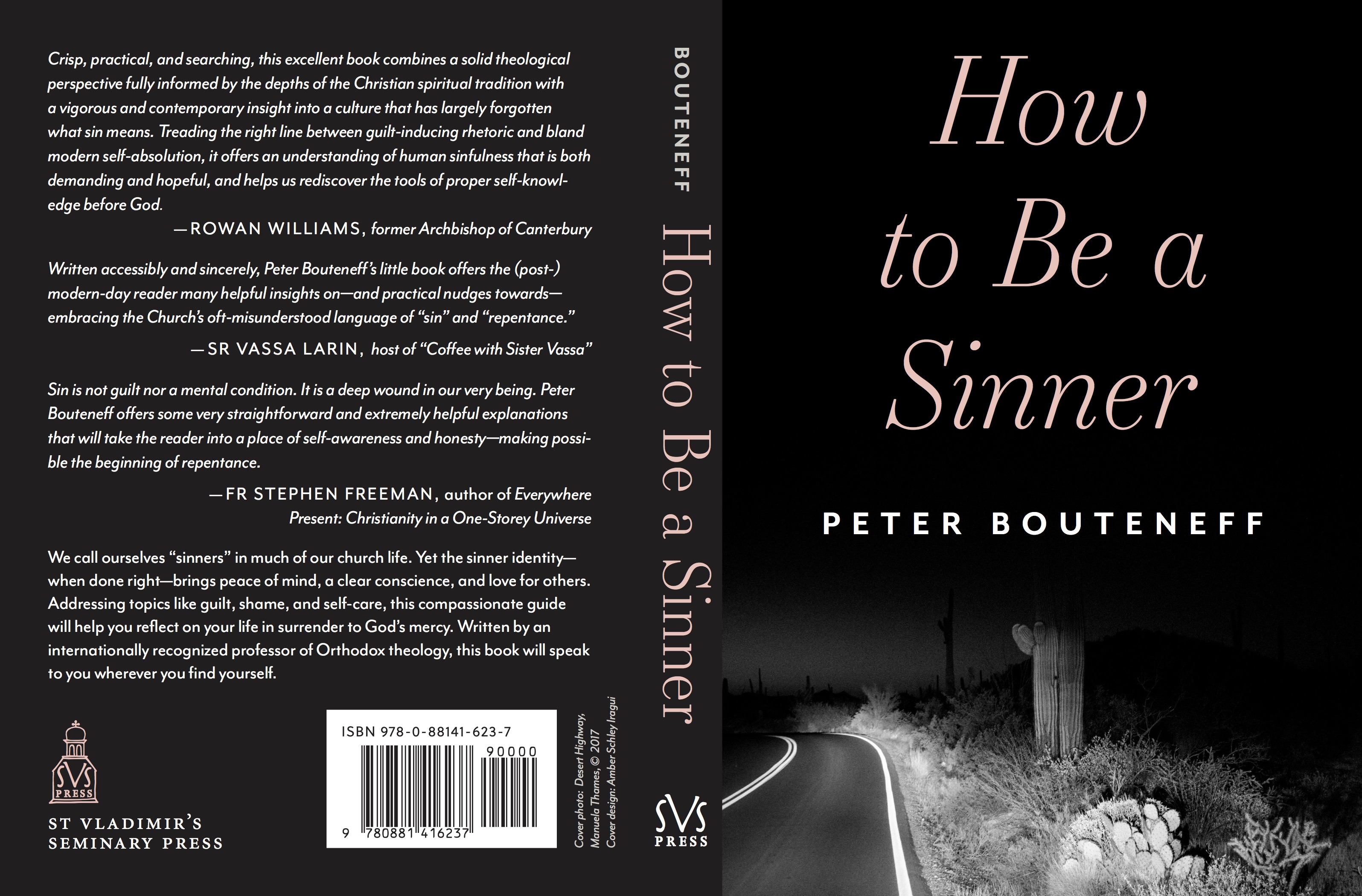

I will be delivering a talk entitled (you guessed it) “How to Be a Sinner” at the

I will be delivering a talk entitled (you guessed it) “How to Be a Sinner” at the