“He was a great poet, perhaps more human than God intended.” This assessment of one of our era’s greatest artists came from someone whom he had harassed sexually. I was struck by this phraseology.

In recent months, the avalanche of revelations and accusations of sexual misconduct have raised many important questions. Among these is whether a great artist’s work can still be admired and even loved when he himself has turned out to be deeply flawed in certain areas of his life. (I say “he” and “him” since sexual harassment is almost exclusively the province of men.)

What struck me in this case was this woman’s comment—about Derek Walcott—that he was great, but “perhaps more human than God intended.” This is a version of the “I’m only human” trope, also found as “all too human” or “to err is human”—the logic being that human beings are so liable to be faulty that humanity itself is defined by deficiency. And that, to me, is a problem.

To be fair, these expressions all have the intention of giving us a break, checking our perfectionism, reducing our unhealthy regret. If it is truly human to “err,” then my error isn’t such a tragedy. And—true enough—everyone does slip up, sometimes innocently, sometimes in a calculated way; with few repercussions or wish disastrous ones. Looking around us and at ourselves, it is impossible to evaluate humanity as perfect or flawless. So, basing ourselves purely on the observation of existing realities, to err is human.

Yet from the Christian perspective, sinning isn’t human at all. We are made in God’s image, and are frequently reminded to be perfect as God is perfect. The Orthodox Church rejects any teaching that we are “totally depraved.” It acknowledges our systemic sin and total dependence upon God, but refuses to say that we are lost to goodness. Humanity, and human beings, are good-but-broken. The distortion of goodness is different from its obliteration.

By now most of us are aware that the Greek for “sin” means “missing the mark,” and in fact a lot of our expressions in English reveal an intuition that humanity is in fact good, at its very root. That’s why we speak of an atrocity or of cruelty as “inhuman,” and why someone who has shown valor or compassion may say about herself “it was the human thing to do.” After all, the word “humane” —which means compassionate, benevolent—comes from the word “human.” Sin isn’t endemic to human nature, it is a distortion of it.

By now most of us are aware that the Greek for “sin” means “missing the mark,” and in fact a lot of our expressions in English reveal an intuition that humanity is in fact good, at its very root. That’s why we speak of an atrocity or of cruelty as “inhuman,” and why someone who has shown valor or compassion may say about herself “it was the human thing to do.” After all, the word “humane” —which means compassionate, benevolent—comes from the word “human.” Sin isn’t endemic to human nature, it is a distortion of it.

But back to the quotation that began my reflection, where someone is assessed for his serious flaws as “perhaps more human than God intended.” That, to me, is an affront on our basic understanding of humanity. Not only is it saying that it’s “human” to be a sexual predator, which is preposterous, it’s also saying that God had intended this person to be somehow better-than-human, and that we’re all disappointed that he turned out to be …human (i.e., a sinner).

Am I being too picky here? Well, I see it this way: until we get it right as to what human beings are, at the root of their nature, we won’t understand sin, virtue, mercy, or salvation.

Today I sent my final manuscript for How to Be a Sinner to the Press. Several friends had read drafts, and most of their comments addressed the tone of my writing, rather than the content. So the Press engaged the best copy-editor I know: Patricia Fann Bouteneff. There were multiple lessons for me to draw, vis-à-vis …humility.

Today I sent my final manuscript for How to Be a Sinner to the Press. Several friends had read drafts, and most of their comments addressed the tone of my writing, rather than the content. So the Press engaged the best copy-editor I know: Patricia Fann Bouteneff. There were multiple lessons for me to draw, vis-à-vis …humility. Etty Hillesum is someone to get to know better. A Dutch Jew during the Nazi period, she became increasingly interested in the Bible and in Russian literature (especially Dostoevsky). Over time, and notably during her time in concentration camps, she kept diaries that would justly earn her the reputation of being a genuine mystic. She knew the darkness within us, better than most. But was always more focused on the light, without losing her realism.

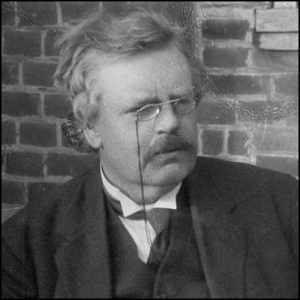

Etty Hillesum is someone to get to know better. A Dutch Jew during the Nazi period, she became increasingly interested in the Bible and in Russian literature (especially Dostoevsky). Over time, and notably during her time in concentration camps, she kept diaries that would justly earn her the reputation of being a genuine mystic. She knew the darkness within us, better than most. But was always more focused on the light, without losing her realism. The 20th-century writer G.K. Chesterton, when asked “What’s wrong with the world?”, had a pretty remarkable answer. He said, “I am.”

The 20th-century writer G.K. Chesterton, when asked “What’s wrong with the world?”, had a pretty remarkable answer. He said, “I am.”